Patients were told for years that cutting calories would ease the symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome. But research suggests dieting may not help at all.

For years, people who had polycystic ovary syndrome and were also overweight were told that their symptoms would improve if they lost weight via a restrictive diet. In 2018, a leading group of PCOS experts recommended that overweight or obese women with the hormonal disorder consider reducing their caloric intake by up to 750 calories a day. That guidance helped to spawn questionable diet programs on social media, and reinforced an impression among people with PCOS that if only they could successfully alter their diets, they would feel better.

But the recommendations were not based on robust PCOS studies, and researchers now say that there is no solid evidence to suggest that a restrictive diet in the long-term has any significant impact on PCOS symptoms. Dieting rarely leads to sustained weight loss for anyone, and for people with PCOS, losing weight is particularly difficult. Beyond that, the link between sustained weight loss and improved symptoms is not very clear or well-established, said Julie Duffy Dillon, a registered dietitian specializing in PCOS care.

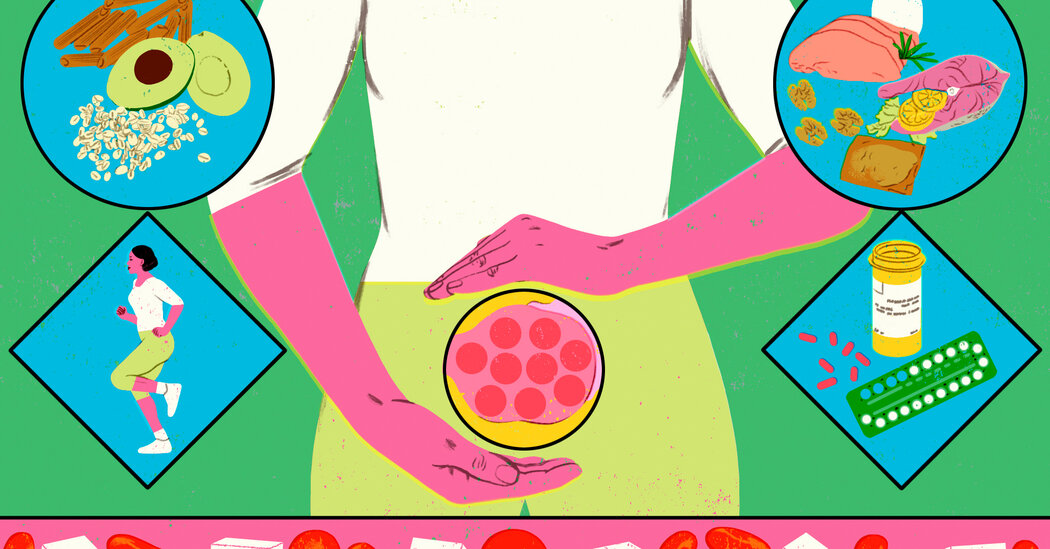

In 2023, the same group, called the International PCOS Network, revised its guidance based on a new analysis of the research and dropped all references to caloric restriction. The group now recommends that people with PCOS maintain an “overall balanced and healthy dietary composition” similar to the Mediterranean diet, which is associated with a reduced risk of the health issues that are linked to the disorder, like cardiovascular disease and diabetes. It’s not known whether eating this way might improve symptoms of PCOS.

The changes in the guidelines reflect “the PCOS literature and the lived experience of people with the condition,” said Dr. Helena Teede, an endocrinologist at Monash Health in Australia and lead author of the 2023 guidelines. “It’s no longer about blaming people or stigmatizing them, or suggesting that it’s their personal behavioral failure that they have higher weight.”

What is PCOS?

PCOS is a hormonal disorder that affects as many as five million women in the United States. It’s characterized by irregular periods, infertility, excessive facial hair growth, acne and scalp hair loss — symptoms that are common with other health conditions, too, making diagnosis tricky. People with PCOS usually ovulate less than once a month and often also have higher levels of androgens (male sex hormones) or multiple underdeveloped follicles on their ovaries (not, as the name suggests, cysts) or both.

Typically, when a woman is experiencing symptoms, a doctor will either scan the ovaries to look for those follicles or draw blood to test hormone levels. There is no cure for PCOS; the first line of treatment is often some form of birth control to help regulate the menstrual cycle.