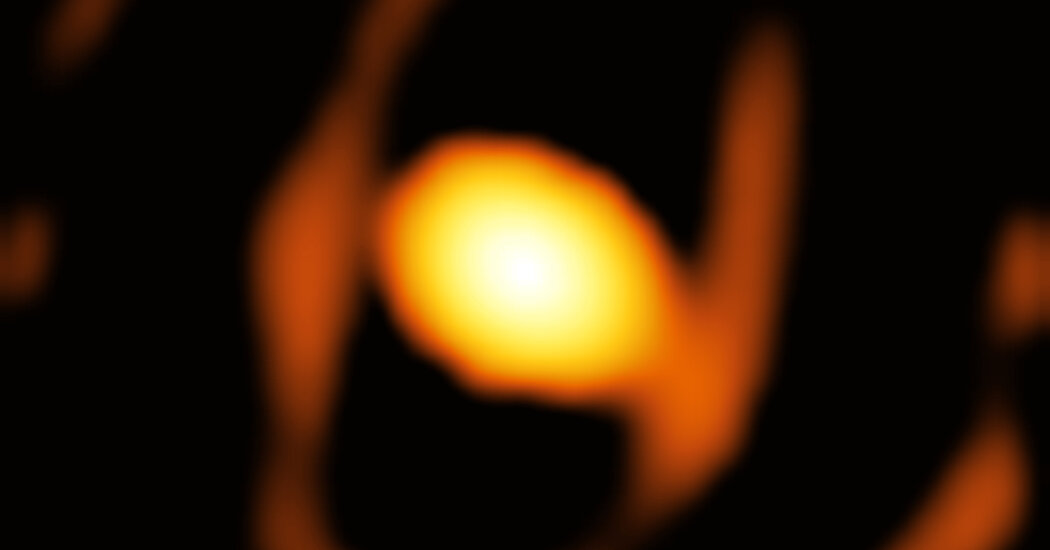

Astronomers zoomed in on a stellar behemoth in the Larger Magellanic Cloud, a galaxy that orbits about 160,000 light-years from the Milky Way.

In a stunning scientific and technological feat, a group of astronomers said Thursday that it had managed to take the first close-up picture of a star in another galaxy. Not only was the image a distance record for such cosmic intimacy, but the star, bulging like an overripe fruit, looks as if it is getting ready to explode.

“For the first time, we have succeeded in taking a zoomed-in image of a dying star in a galaxy outside our own Milky Way,” Keiichi Ohnaka, an astrophysicist from Andrés Bello National University in Chile, said in a news release from the European Southern Observatory, an international collaboration that runs a phalanx of powerful telescopes in Chile.

Dr. Ohnaka and colleagues described their observations in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

The star goes by the name of WOH G64. It is in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a small galaxy that orbits the Milky Way at a distance of about 160,000 light-years and is visible as a large cloud of light in the Southern Hemisphere. The L.M.C. was the site of the last great supernova explosion witnessed by astronomers in 1987, an event known as SN1987a.

Observations with a spacecraft called the Infrared Astronomical Satellite in the 1980s revealed that WOH G64, once thought to be cool and dim, is actually the most luminous red supergiant star in that galaxy, a behemoth at least 2,000 times bigger than the sun.

When such big stars finally run out of the thermonuclear fuel that keeps their inner fires burning, their cores collapse. Some particularly massive stars vanish without further ado into black holes. But others rebound and explode as supernovas, spewing newly created elements into space to seed new stars and planets before settling into their final states as black holes or tiny dense neutron stars.