Some of the problems that patients ran into, including a lack of insurance coverage, have been resolved.

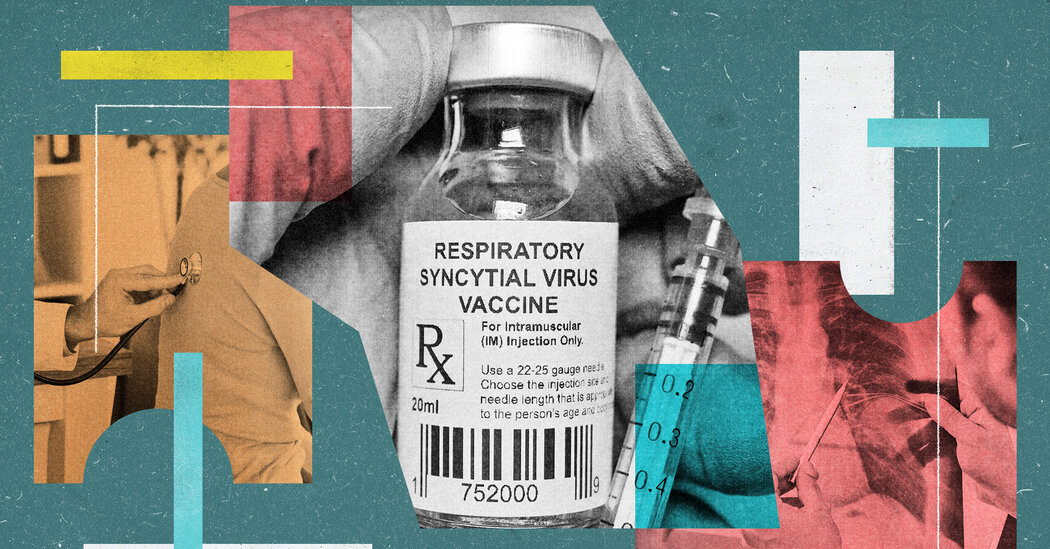

When the Food and Drug Administration approved several new vaccines against respiratory syncytial virus last year, the shots were celebrated as a “powerful new tool” to protect infants and older people. Pharmaceutical giants projected billions of dollars in sales, assuming a large swath of the eligible population would roll up their sleeves.

But for all the anticipation, relatively few people sought the vaccines out: Only about 24 percent of eligible older adults received it last season. It was a disappointing response, one experts blamed largely on vaccine fatigue, the cost of the shots and confusion over who should get them.

This season, however, promises to be different. Drugmakers have ramped up manufacturing of a treatment for infants that was in short supply last year, and more insurers are now covering R.S.V. shots. But experts said there are still hurdles that must be overcome to increase vaccination rates, including sharpening public health messaging and increasing the public’s understanding of how serious the virus can be for certain groups.

The Risks of R.S.V.

Most people with R.S.V. only experience mild symptoms, like a runny nose or a cough. However, for infants and older adults, especially those who are immunocompromised or have chronic conditions like heart or lung disease, a bout of R.S.V. can be serious.

There are up to 160,000 hospitalizations and 10,000 deaths from R.S.V. among older adults in the United States each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The virus is the leading cause of hospitalization in infants in their first year of life. Babies with R.S.V. can develop pneumonia and often need treatment with oxygen, IV fluids and mechanical ventilation to support their breathing. The virus can also be dangerous to some young children: Between 100 and 300 children under age 5 die each year of R.S.V.