Deepali Misra-Sharp

Deepali Misra-SharpThis is the fifth feature in a six-part series that is looking at how AI is changing medical research and treatments.

The difficulty of getting an appointment with a GP is a familiar gripe in the UK.

Even when an appointment is secured, the rising workload faced by doctors means those meetings can be shorter than either the doctor or patient would like.

But Dr Deepali Misra-Sharp, a GP partner in Birmingham, has found that AI has alleviated a chunk of the administration from her job, meaning she can focus more on patients.

Dr Mirsa-Sharp started using Heidi Health, a free AI-assisted medical transcription tool that listens and transcribes patient appointments, about four months ago and says it has made a big difference.

“Usually when I’m with a patient, I am writing things down and it takes away from the consultation,” she says. “This now means I can spend my entire time locking eyes with the patient and actively listening. It makes for a more quality consultation.”

She says the tech reduces her workflow, saving her “two to three minutes per consultation, if not more”. She reels off other benefits: “It reduces the risk of errors and omissions in my medical note taking.”

With a workforce in decline while the number of patients continues to grow, GPs face immense pressure.

A single full-time GP is now responsible for 2,273 patients, up 17% since September 2015, according to the British Medical Association (BMA).

Could AI be the solution to help GP’s cut back on administrative tasks and alleviate burnout?

Some research suggests it could. A 2019 report prepared by Health Education England estimated a minimal saving of one minute per patient from new technologies such as AI, equating to 5.7 million hours of GP time.

Meanwhile, research by Oxford University in 2020, found that 44% of all administrative work in General Practice can now be either mostly or completely automated, freeing up time to spend with patients.

Corti

CortiOne company working on that is Denmark’s Corti, which has developed AI that can listen to healthcare consultations, either over the phone or in person, and suggest follow-up questions, prompts, treatment options, as well as automating note taking.

Corti says its technology processes about 150,000 patient interactions per day across hospitals, GP surgeries and healthcare institutions across Europe and the US, totalling about 100 million encounters per year.

“The idea is the physician can spend more time with a patient,” says Lars Maaløe, co-founder and chief technology officer at Corti. He says the technology can suggest questions based on previous conversations it has heard in other healthcare situations.

“The AI has access to related conversations and then it might think, well, in 10,000 similar conversations, most questions asked X and that has not been asked,” says Mr Maaløe.

“I imagine GPs have one consultation after another and so have little time to consult with colleagues. It’s giving that colleague advice.”

He also says it can look at the historical data of a patient. “It could ask, for example, did you remember to ask if the patient is still suffering from pain in the right knee?”

But do patients want technology listening to and recording their conversations?

Mr Maaløe says “the data is not leaving system”. He does say it is good practice to inform the patient, though.

“If the patient contests it, the doctor cannot record. We see few examples of that as the patient can see better documentation.”

Dr Misra-Sharp says she lets patients know she has a listening device to help her take notes. “I haven’t had anyone have a problem with that yet, but if they did, I wouldn’t do it.”

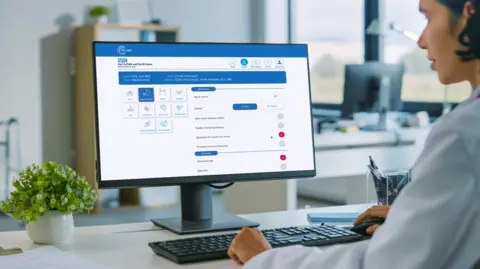

C the signs

C the signsMeanwhile, currently, 1,400 GP practices across England are using the C the Signs, a platform which uses AI to analyse patients’ medical records and check different signs, symptoms and risk factors of cancer, and recommend what action should be taken.

“It can capture symptoms, such as cough, cold, bloating, and essentially in a minute it can see if there’s any relevant information from their medical history,” says C the Signs chief executive and co-founder Dr Bea Bakshi, who is also a GP.

The AI is trained on published medical research papers.

“For example, it might say the patient is at risk of pancreatic cancer and would benefit from a pancreatic scan, and then the doctor will decide to refer to those pathways,” says Dr Bakshi. “It won’t diagnose, but it can facilitate.”

She says they have conducted more than 400,000 cancer risk assessments in a real-world setting, detecting more than 30,000 patients with cancer across more than 50 different cancer types.

An AI report published by the BMA this year found that “AI should be expected to transform, rather than replace, healthcare jobs by automating routine tasks and improving efficiency”.

In a statement, Dr Katie Bramall-Stainer, chair of General Practice Committee UK at the BMA, said: “We recognise that AI has the potential to transform NHS care completely – but if not enacted safely, it could also cause considerable harm. AI is subject to bias and error, can potentially compromise patient privacy and is still very much a work-in-progress.

“Whilst AI can be used to enhance and supplement what a GP can offer as another tool in their arsenal, it’s not a silver bullet. We cannot wait on the promise of AI tomorrow, to deliver the much-needed productivity, consistency and safety improvements needed today.”

Alison Dennis, partner and co-head of law firm Taylor Wessing’s international life sciences team, warns that GPs need to tread carefully when using AI.

“There is the very high risk of generative AI tools not providing full and complete, or correct diagnoses or treatment pathways, and even giving wrong diagnoses or treatment pathways i.e. producing hallucinations or basing outputs on clinically incorrect training data,” says Ms Dennis.

“AI tools that have been trained on reliable data sets and then fully validated for clinical use – which will almost certainly be a specific clinical use, are more suitable in clinical practice.”

She says specialist medical products must be regulated and receive some form of official accreditation.

“The NHS would also want to ensure that all data that is inputted into the tool is retained securely within the NHS system infrastructure, and is not absorbed for further use by the provider of the tool as training data without the appropriate GDPR [General Data Protection Regulation] safeguards in place.”

For now, for GPs like Misra-Sharp, it has transformed their work. “It has made me go back to enjoying my consultations again instead of feeling time pressured.”