A Public Health Service employee, he turned whistle-blower after learning of decades-long research involving hundreds of poor, infected Black men who were left untreated.

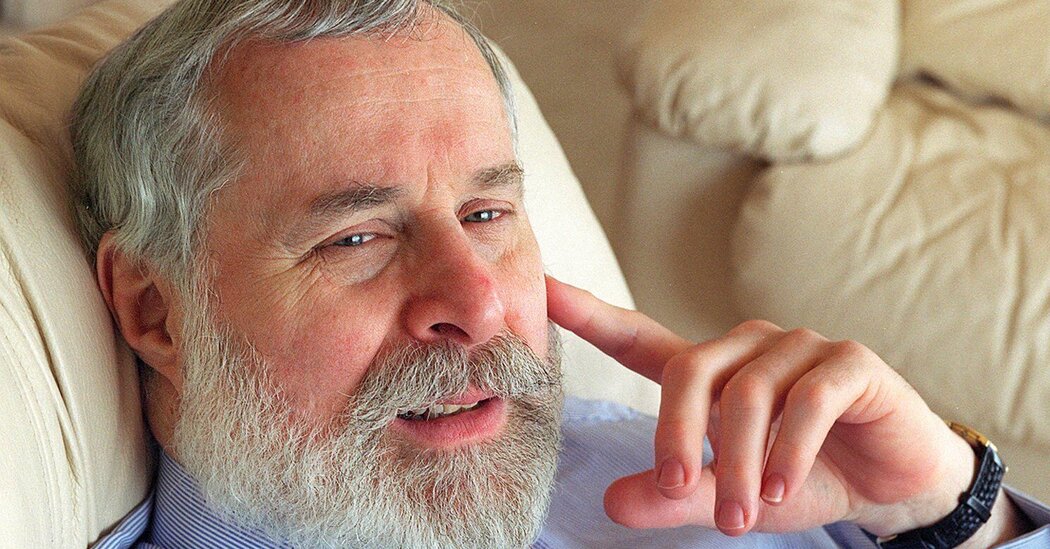

Peter Buxtun, a whistle-blower who in 1972 exposed a 40-year government experiment to track the effects of syphilis in Black men in Alabama — who were neither told that they had the disease nor offered treatment — died on May 18 in Rocklin, Calif., near Sacramento. He was 86.

His death, in a memory care center, was from complications of Alzheimer’s disease, said John K. Seidts, a close friend. The death was first reported on Monday by The Associated Press, to which Mr. Buxtun had turned over his files and which in 1972 published the first news articles about his disclosures.

Exposure of the Tuskegee Study, as the federal research was known, created a political furor that shut it down, but the study cast a long, dark shadow as an episode of official racism embedded in government policy. It was one of the worst medical ethics scandals in U.S. history, tarnishing the do-no-harm image of doctors and, especially, sowing mistrust of the medical establishment among many African Americans.

Mr. Buxtun, the son of a Jewish father who fled Czechoslovakia before World War II to escape persecution, was working as a venereal disease investigator for the U.S. Public Health Service in San Francisco in 1965 when he overheard a co-worker talking about the Tuskegee Study taking place in rural Alabama.

One of his first acts was to visit a library to research the crimes of Nazi doctors in World War II.

He contacted the Communicable Disease Center in Atlanta (now the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), which had cooperated with the Public Health Service in overseeing the Tuskegee Study. The agency, making no effort to conceal the study from a government employee, sent him a manila envelope stuffed with reports.