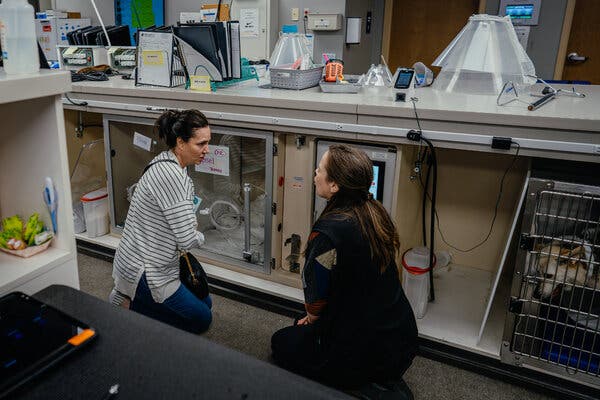

Amy Conroy sat alone in a veterinary exam room, hands clutching a water bottle, eyes blinking back tears. Her 16-year-old cat, Leisel, had been having trouble breathing. Now, she was waiting for an update.

The door opened, and Laurie Maxwell came in.

Ms. Maxwell works for MedVet, a 24-hour emergency veterinary hospital in Chicago. But when she took a seat opposite Ms. Conroy on a Monday evening in May, she explained that she wasn’t there for the cat. She was there for Ms. Conroy.

Ms. Maxwell is a veterinary social worker, a job in a little-known corner of the therapy world that focuses on easing the stress, worry and grief that can arise when a pet needs medical care.

Pets no longer exist at the periphery of the human family — to take one example, a survey in 2022 found that almost half of Americans sleep with an animal in their bed. As that relationship has intensified, so has the stress when something goes wrong. Those emotions can spill over at animal hospitals, where social workers can help pet owners work through difficult choices, such as whether to euthanize a pet or whether they can afford to pay thousands of dollars for their care.

Though still rare, social workers in animal hospitals are growing in their ranks. Large chains, like VCA, are beginning to employ them, as are major academic veterinary hospitals. The service is typically offered for free. About 175 people have earned a certification in veterinary social work from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, which is a center for the field.