Researchers analyzed a skull found in Montana of a plant-eating member of the ceratops family, finding distinct traits.

In the Late Cretaceous period, a remarkable flowering of horned dinosaurs occurred along the coastal floodplains of western North America. Two different families — each sporting every imaginable combination of spikes, horns and frills — diversified across the landscape, using their headgear to signal mates and challenge rivals.

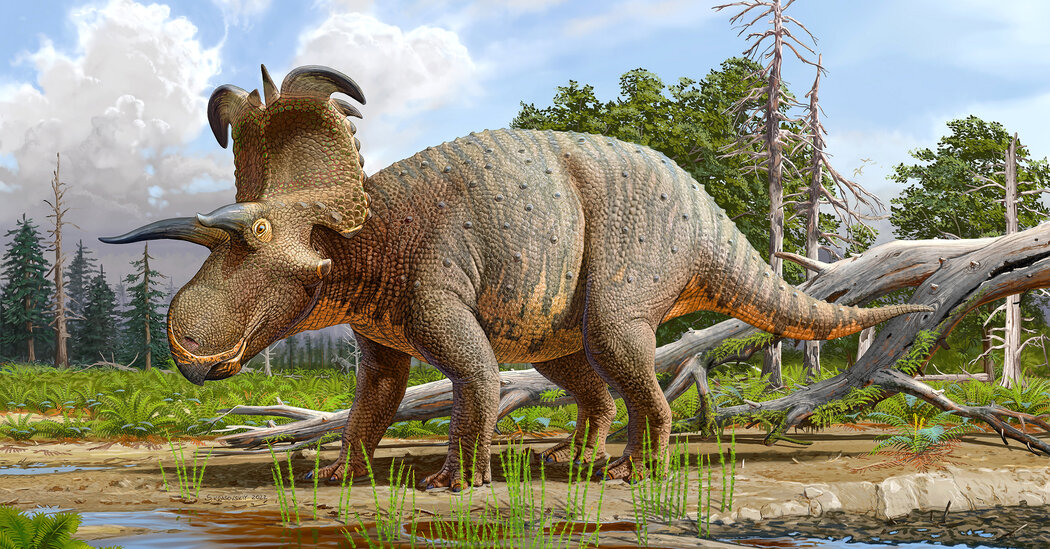

Seventy-eight million years later, members of that ancient profusion are still turning up, leading to a modern boom in discoveries. The newest — described on Thursday by a team of researchers in the journal PeerJ — is Lokiceratops rangiformis, a five-ton herbivore with spectacular, curving brow horns and huge, bladed spikes on its meter-long frill.

The researchers argue that this is a new species, and with others like it suggest that the area from Mexico to Alaska was full of pockets of local dinosaur biodiversity. Other experts, though, contend that there is not enough evidence to draw such conclusions based on one set of remains.

The skull of the dinosaur in question was discovered in 2019 by a commercial paleontologist on private land in northern Montana. It was acquired by the Museum of Evolution in Maribo, Denmark.

“They saved it by purchasing it, so now it’s available in perpetuity for scientists to look at it,” said Joseph Sertich, a paleontologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and an author of the study. “We couldn’t write a paper on a fossil sitting in a rich person’s living room and being treated as art.”

The team of researchers initially believed they were working with the remains of a Medusaceratops. But as they clicked together pieces of the shattered skull, they began to notice differences.