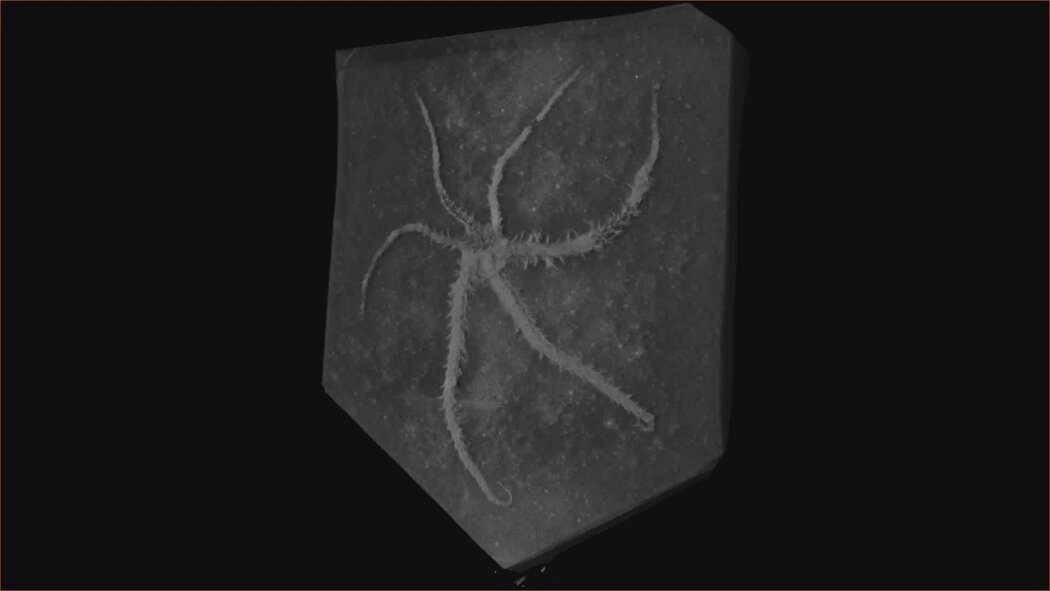

The brittle star specimen suggests that the sea creatures have been splitting themselves in two to reproduce for more than 150 million years.

Some brittle stars give an arm and a leg (and still another appendage) to reproduce. When mates are scarce, these starfish-like sea creatures split themselves in half. Each side then regrows its missing half, creating two identical clones of the original animal.

This process, known as clonal fragmentation, is practiced by almost 50 species of existing brittle stars and their starfish relatives. However, scientists have found it difficult to determine when brittle stars, a gangly group of echinoderms, started reproducing this way.

A recently discovered fossil from Germany pushes the origin of cloning sea stars back more than 150 million years. In a paper published Wednesday in The Proceedings of the Royal Society B, a team of scientists describe the fossil of a brittle star that was petrified while regenerating three of its six limbs.

“It’s the first fossil evidence for this phenomenon,” said Ben Thuy, a paleontologist at the National Museum of Natural History in Luxembourg and an author of the new study. The specimen, he added, shows that “clonal fragmentation is actually much older than people previously thought.”

The brittle star fossil was discovered in the Nusplingen limestone deposit in southern Germany. In the late Jurassic period, 155 million years ago, this area was a balmy lagoon home to marine crocodiles, sharks and pterosaurs. When some of these creatures died, they sank to the bottom and were buried by mud. Low oxygen levels slowed their decomposition, preventing scavengers from picking at the carcasses.

These conditions preserved fossils in incredible detail, capturing delicate structures like dragonfly wings and even a dinosaur feather. The newly described brittle star is another treasure imprinted onto the site’s limestone slabs. “You have this brittle star with every single piece in its original place, just as if it washed up on the beach a day ago,” Dr. Thuy said.