By digging into the geologic record, scientists

are learning how wildfires shaped —

and were shaped by — climate change long ago.

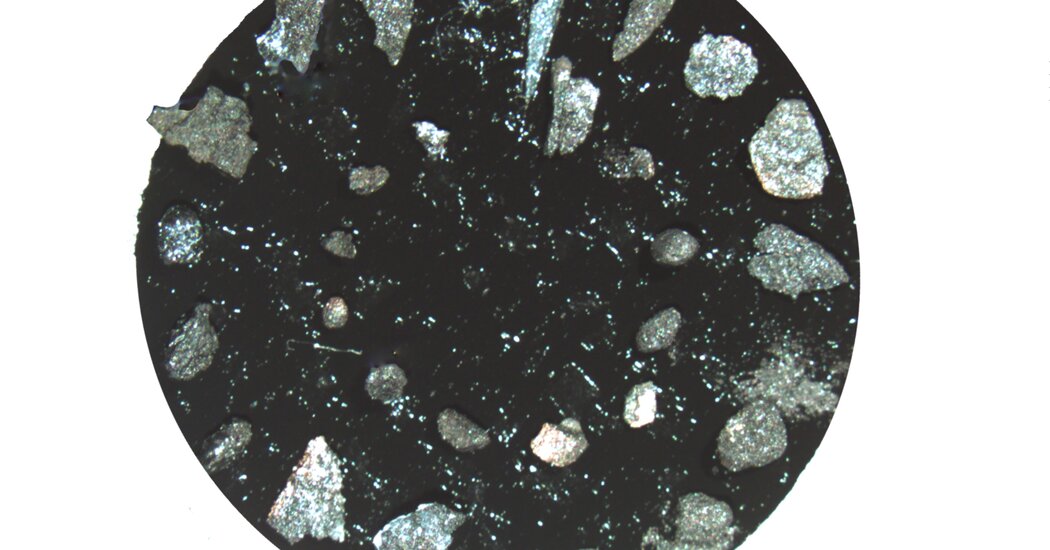

The oldest evidence of wildfire in the world can be found in a laboratory on the fourth floor of a brick building in Waterville, Maine. To the untrained eye, it looks like a speck of black lint, not much larger than the tip of a pin. To Ian J. Glasspool, a paleobotanist at Colby College, it is a 430-million-year-old piece of charcoal.

The specimen, which Dr. Glasspool discovered in a mudstone from southern Wales, is one of many pieces of ancient charcoal that have been studied in recent years to explore how fires burned in the past. Together, these remnants are helping scientists understand how fires have shaped and been shaped by environmental change through geologic time.

“They are tedious-looking things,” Dr. Glasspool said, lifting a sample embedded in a small resin disc. “But there’s a whole heap you can get out of them.”

These ancient insights may not help us manage individual wildfires today, Dr. Glasspool said. But they can provide a clearer sense of the global phenomenon of fire and how it shapes Earth’s climate. This, in turn, can help modelers make more accurate projections of the future climate.

“The geologic record shows that it is a lot more complicated than ‘it gets hot, there will be more fires,’” said Jennifer M. Galloway, a paleoecologist with the Geological Survey of Canada. Dr. Galloway recently published a paper in the journal Evolving Earth on the merits of studying ancient wildfires as a way to understand climate dynamics today.