After her own mastectomy, sociologist Sarah Thornton sought to answer the question.

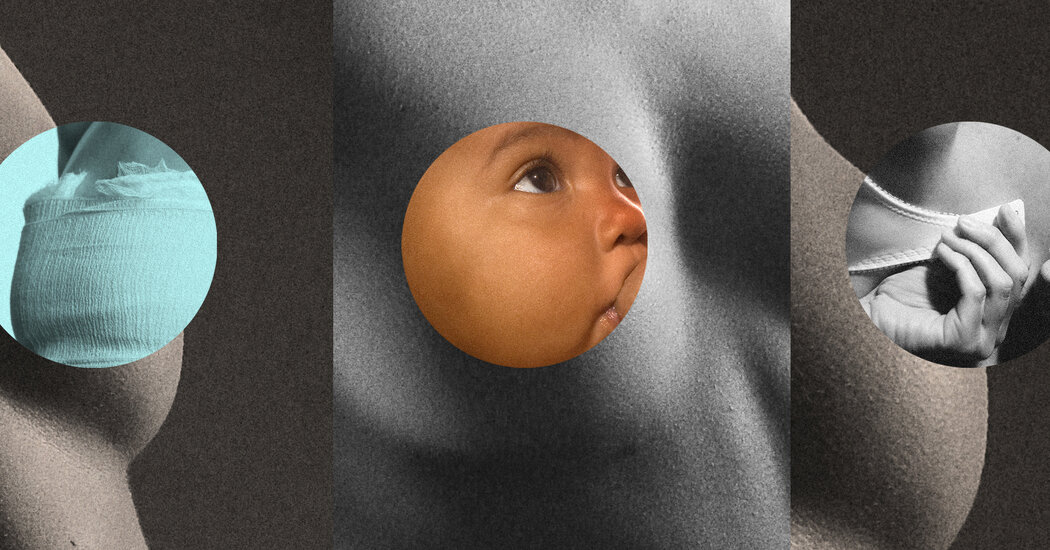

The day before her double mastectomy surgery six years ago, the author and cultural sociologist Sarah Thornton let her breasts free. She went swimming in an outdoor pool in the San Francisco Bay Area and untied her bikini top, allowing her 34Bs to sway in the water and soak up the sunshine. It was her way of saying goodbye to them, she said in a recent interview.

“I was someone who kind of dismissed them as just dumb boobs, irrelevant, not important,” she said. As a self-proclaimed feminist, she used to think that any obsession with breasts was vain and distasteful, driven by a superficial need to please the male gaze. Her own breasts were the focus of two sexual harassment incidents in her teens, and, about a decade ago, they became a source of fear: Breast cancer ran in the family and doctors discovered atypical cells. After much prodding and testing, getting rid of a part of her body that she wasn’t particularly attached to seemed like an easy precaution to take.

But months after her surgery, which included getting implants that felt like “silicone impostors” — so foreign and inanimate to her that she felt compelled to give them the names Bert and Ernie — she became “just a total muddle of emotions around what I lost and what I gained,” she said. “Bert and Ernie were really weird for me — they were larger than I’d ever had before, they were hard, I had no nipple sensation anymore.” (For our video interview, Thornton wore a crew neck T-shirt with a drawing of Bert, Ernie and other Sesame Street residents across her chest). It was then that she realized she hadn’t appreciated her breasts enough.

Thornton’s exploration into the cultural significance of breasts resulted in her new book, “Tits Up: What Sex Workers, Milk Bankers, Plastic Surgeons, Bra Designers, and Witches Tell Us About Breasts,” which will be published on May 7. “Tits,” she writes, is her preferred word; “breasts” sounds sterile and is associated with cancer and feeding, while “boobs” suggests unseriousness, like “booby prize” or “booby trap.”

Thornton wrote the book “in order to help women reappraise their chests in positive ways, and men, too,” she said. “Actually, I would really like men to read the book because so many of them think they really know about tits.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How do you feel about ‘Bert’ and ‘Ernie’ now, after writing this book?