The low water levels that choked cargo traffic were more closely tied to the natural climate cycle than to human-caused warming, a team of scientists has concluded.

The recent drought in the Panama Canal was driven not by global warming but by below-normal rainfall linked to the natural climate cycle El Niño, an international team of scientists has concluded.

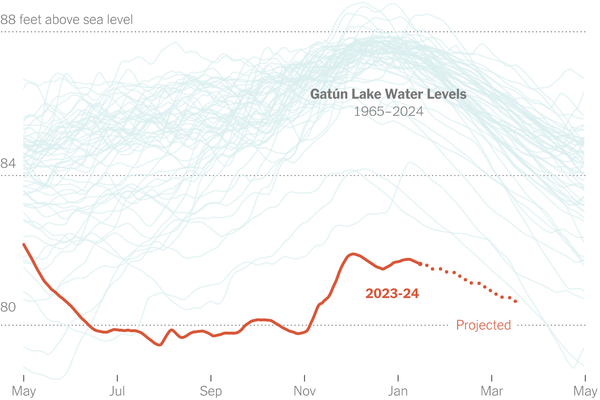

Low reservoir levels have slowed cargo traffic in the canal for most of the past year. Without enough water to raise and lower ships, officials last summer had to slash the number of vessels they allowed through, creating expensive headaches for shipping companies worldwide. Only in recent months have crossings started to pick up again.

The area’s water worries could still deepen in the coming decades, the researchers said in their analysis of the drought. As Panama’s population grows and seaborne trade expands, water demand is expected to be a much larger share of available supply by 2050, according to the government. That means future El Niño years could bring even wider disruptions, not just to global shipping, but also to water supplies for local residents.

“Even small changes in precipitation can bring disproportionate impacts,” said Maja Vahlberg, a risk consultant for the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Center who contributed to the new analysis, which was published on Wednesday.

Panama, in general, is one of the wettest places on Earth. On average, the area around the canal gets more than eight feet of rain a year, almost all of it in the May-to-December wet season. That rain is essential both for canal operations and for the drinking water consumed by around half of the country’s 4.5 million people.