A new study resets the timing for the emergence of bioluminescence back to millions of years earlier than previously thought.

Bioluminescence is used throughout the animal kingdom, particularly in marine environments, to lure prey, startle predators and even act as camouflage in the surrounding light.

“We always say it’s light-limited in the deep sea, but there are a lot of organisms that produce their own light,” said Andrea Quattrini, a zoologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington.

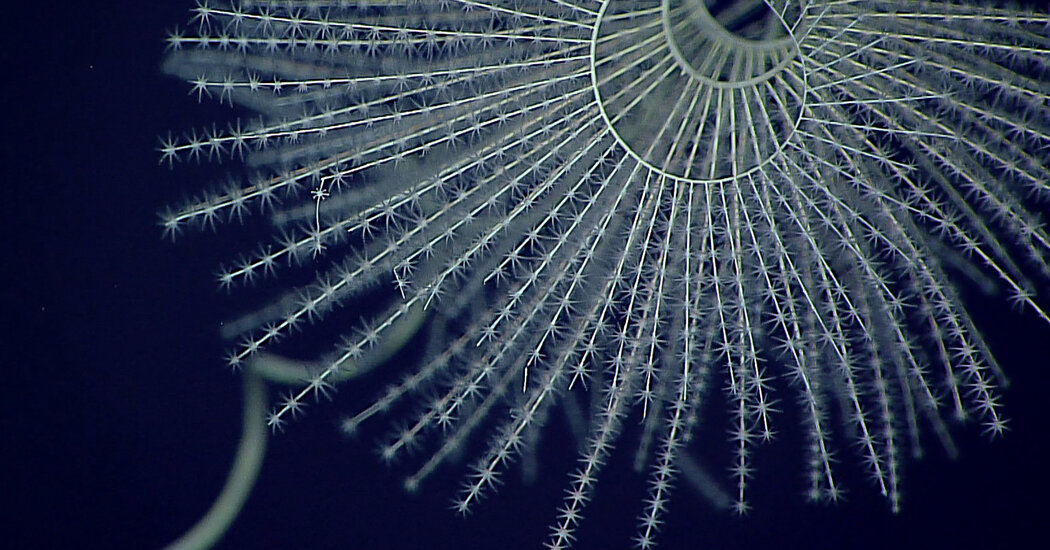

The dazzling glow of bioluminescence is common in Octocorallia, also known as octocorals, a class of over 3,000 Anthozoa species including sea fans, sea pens and soft corals. The prevalence of bioluminescence in these sessile animals makes a lot of sense, Dr. Quattrini said: “They settle somewhere and they’re there.”

How long organisms have been able to emit light is at the center of recent research by Dr. Quattrini and colleagues. Their latest study, published Tuesday in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, resets the timing for the emergence of bioluminescence back to about 540 million years ago, from the existing understanding that it appeared in small marine crustaceans 267 million years ago.

The researchers based their finding on recent octocoral evolutionary tree work, octocoral fossils and modeling to trace the ancestral past of the tiny organisms.

Bioluminescence is believed to have evolved nearly 100 times across history, caused by a simple chemical reaction, when a light-producing molecule called a luciferin reacts with an enzyme called luciferase.