Astronomers have gotten better at tracking the motions of stars just beyond the solar system. But that’s made it harder to predict Earth’s future and reconstruct its past.

Regardless of what stock market analysts, political pollsters and astrologers might say, we can’t predict the future. In fact, we can’t even predict the past.

So much for the work of Pierre-Simon Laplace, the French mathematician, philosopher and king of determinism. In 1814, LaPlace declared that if it were possible to know the velocity and position of every particle in the universe at one particular moment — and all the forces that were acting on them — “for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain, and the future, just like the past, would be the present to it.”

Laplace’s dream remains unfulfilled because we can’t measure things with infinite precision, and so tiny errors propagate and accumulate over time, leading to ever more uncertainty. As a result, in the 1980s astronomers including Jaques Laskar of the Paris Observatory concluded that computer simulations of the motions of the planets could not be trusted when applied more than 100 million years into the past or future. By way of comparison, the universe is 14 billion years old and the solar system is about five billion years old.

“You can’t cast an accurate horoscope for a dinosaur,” Scott Tremaine, an orbital dynamics expert at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., commented recently in an email.

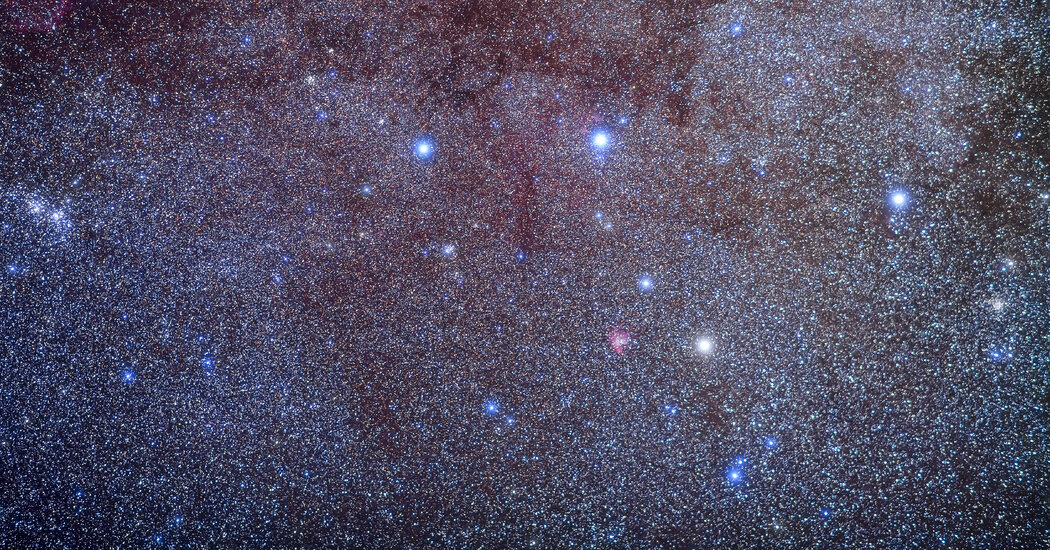

The ancient astrological chart has now become even blurrier. A new set of computer simulations, which take into account the effects of stars moving past our solar system, has effectively reduced the ability of scientists to look back or ahead by another 10 million years. Previous simulations had considered the solar system as an isolated system, a clockwork cosmos in which the main perturbations to planetary orbits were internal, resulting from asteroids.

“The stars do matter,” said Nathan Kaib, a senior scientist with the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Ariz. He and Sean Raymond of the University of Oklahoma published their results in Astrophysical Journal Letters in late February.