-

Published24 September 2023

The number of people in hospital has gone up. Google searches have doubled in a month and booster vaccines have been brought forward because of a new variant. It might all feel a bit 2021. But – these days – how much do we really need to worry about Covid?

Marjorie from Pembrokeshire had gone through the whole pandemic without catching the virus – until this month.

“I thought I had natural immunity,” she says.

“But I caught it from my granddaughter who had the same symptoms as mine.”

In her case, that meant a headache, muscle pain and a loss of smell and taste.

“I just didn’t realise I would feel so weak and lethargic,” she adds.

How many people – like Marjorie – are catching Covid this autumn is impossible to know for sure.

All those drive-in testing sites are long closed and those free boxes of lateral flow tests probably dried up months ago.

The Office for National Statistics infection survey, which used to test a random sample of the population, was scrapped back in March.

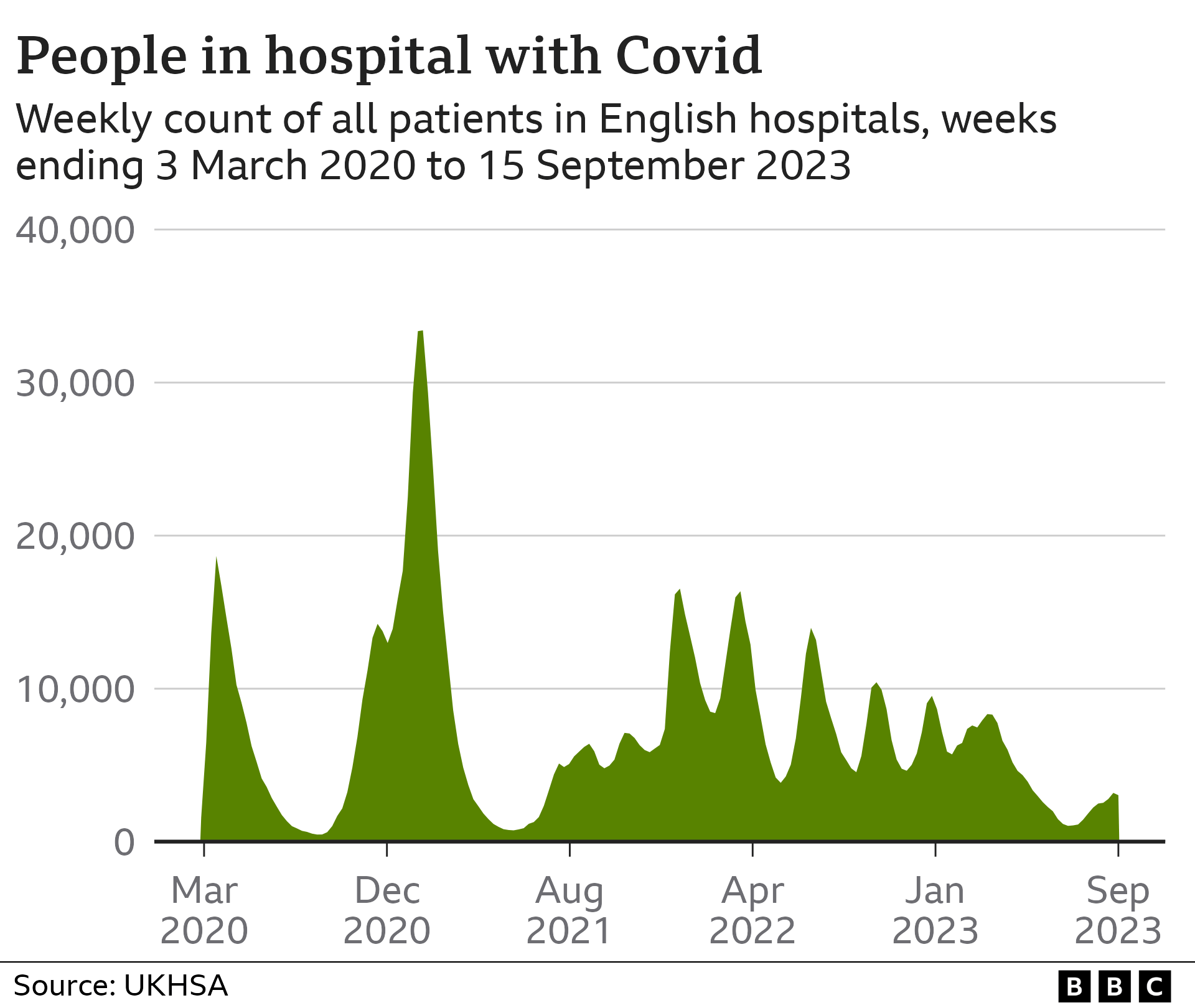

But we do still record the number of people who test positive in hospital across the whole UK, and that figure has been creeping up since the summer.

“What does it tell me about the virus? It tells me it’s spreading and it tells me it still has the ability to make people very unwell,” says Stuart McDonald, an actuary at the consultants LCP, who has studied the data closely since the start of the pandemic.

On 17 September, 3,019 hospital beds in England were taken up by someone with Covid. That number has tripled since July, but dipped last week, and is just a fraction of the 33,000 seen at the peak of the second wave in 2021.

About a third of those patients were being treated mainly for the disease, with most testing positive after they were admitted for another reason.

Why do some people get infected?

Hospital trends give us a very rough idea of how much virus is around and whether infection levels are rising or falling.

How likely we are to catch it, and how sick we get, then depends on a mix of complex factors – from genetics and age, to lifestyle and the environment in which we live.

Research published in the journal Nature this year suggests about 10% of the population carry a gene which allows them to identify and eliminate the virus before they even start to develop tell-tale symptoms like a cough, sore throat or fever.

-

93%aged 12+ have received at least one vaccine

-

82%infected at least once by Nov 2022

Source: NHS Digital, ONS

We have all built up different levels of immunity over the last four years depending on our vaccine record and contact with the disease.

“There’s probably no two people in the country whose history of vaccinations and Covid exposure are alike,” says Mr McDonald.

“So I think it’s more difficult to predict what will come next than it has been at any previous point.”

That immunity starts to fall soon after an infection or a vaccine. This is where the virus differs from measles or polio, for example, where jabs in childhood can protect you for life.

Protection against catching Covid is likely to last just a few months – at best – although data shows protection against severe disease is more long-lasting.

In part that is because the virus itself is constantly changing.

Previous waves have been driven by different forms – or variants – which have undergone multiple genetic changes.

Those mutations can alter the virus’s behaviour – making it spread faster, for example.

But crucially they might also make it harder for our immune systems, which have been primed to respond to those older versions, to recognise and fight off.

In late 2021, the Omicron variant did just that and infected millions, although that wave did not lead to a huge spike in hospitalisations and deaths.

“Being exposed to the virus, either through vaccination, infection or a combination of both, is undoubtedly reducing the severity of disease when we get it,” says Alex Richter, a professor of clinical immunology at the University of Birmingham.

More recently we have seen a series of smaller waves driven by close relatives – or subvariants – of Omicron.

-

18countries with confirmed cases

-

54cases detected in the UK

-

28infections at Norfolk case home

-

0residents needed hospital treatment for Covid

Source: GISAID, UKHSA, PHS

In August 2023, scientists around the world started tracking the spread of yet another version with a large number of mutations.

Just 54 cases of BA.2.86, as it is now called, have been confirmed in the UK, including a large outbreak at a care home in Norfolk. Early lab tests appear to be reassuring – with signs it may be less contagious and immunity dodging than some originally feared.

How well protected are we?

The emergence of BA.2.86 meant a decision was made to bring forward the autumn Covid booster to better protect the most vulnerable this winter.

But the new jabs are only available to people over 65 years old – it was the over-50s last year – and those with certain health conditions. That is a tactical decision, says Dr Adam Finn, professor of paediatrics at the University of Bristol.

He explained: “When younger people who’ve already had infections and vaccines get Covid [again], they get a cold and a cough and might be off work for a few days.

“There’s no real value in investing a lot of time and effort immunising them again when there are so many other things for the health service to be doing.”

The reality is then that most under-65s will now end up boosting their immunity not through vaccination, but through catching Covid many times.

How worried should we be?

Prof Richter says it is now time to start thinking of Covid more like flu, where new forms of the disease, some worse than others, appear every year and new vaccines are rolled out for the latest winter strain.

Covid will still be a problem for the most vulnerable, she adds, and hospitals, which will still need to deal with new infection waves.

“We have bad flu years and good flu years,” she says.

“There’s a good chance that once every four or five years, we’re going to have a bad dose [of Covid] and we are going to need to go to bed for a few days, otherwise most of the time, for most of us, I think it will be OK.”

Every dose of the virus is not completely without danger, even for the healthy, with some research suggesting an increased risk of long-Covid symptoms like fatigue, shortness of breath and brain fog.

But – in general – Prof Finn says each new infection should feel milder with the length of time you are sick reduced.

“Each time you catch it, your immunity gets stronger and broader,” he adds.

Sam, an IT worker from north London, managed to pick up infection number three on a trip to Turkey with her family this month.

“The first time was really horrible, the second time it felt like flu, but by the third time I didn’t really think about it,” she says.

“I just had a stinker of a cold and was all bunged up.”

This is maybe what scientists meant when, at the very start of the pandemic, we were told that, one day, we would have to learn to live with Covid.

The virus is not going away.

But perhaps it is starting to become part of the background to our everyday lives.

-

-

Published18 September 2023

-

-

-

Published20 December 2023

-