It is midnight in central London and the rain is bouncing off the ground.

Most of the city is asleep, but on an athletics track just south of the River Thames one man – shivering and soaked to the bone in shorts, T-shirt and makeshift gilet fashioned from a black bin bag – is running laps.

A pensioner, who flew in from Norway that morning, is doing the same in a blue pound-shop poncho.

There is a small pile of vomit on the inside of the track, where a runner emptied his stomach an hour earlier. Job done, he picked himself up and carried on.

Plenty of others have also been sick, including a 74-year-old former librarian. Twice.

It is hardly a surprise. After all, these people have been running around the same track for 12 hours. They have another 12 to go.

Welcome to the world of 24-hour racing, where the boundaries of pain, pleasure and possibility are redefined by a special band of runners who are as exceptional as they are utterly normal.

The format could not be simpler: complete as many laps of the 400m track as you can in 24 hours and whoever clocks up the most miles wins.

But as the puddles swell and the temperature drops in the small hours at Battersea Park Athletics Club, the only thing on runners’ minds is survival.

So why do people choose to do this? What keeps them going when their body – and mind – is at breaking point? And how far can a human actually run in 24 hours?

“If there’s one thing we’ve got in common it’s that we’re all weird,” says former British record holder Robbie Britton, who has run 12 24hr races.

“You’re going to have a minimum of 12 hours of pain. There’s no other sport where you get to the start line the fittest you’ve ever been and, if all goes well, you can’t walk properly the next day.”

Aleksandr Sorokin is no different. “Absolutely I don’t enjoy it. I hate it because I know it’s big suffering,” says the man who ran 198 miles to break his own world record in 2022. That is the equivalent of more than seven marathons at 3hr 10min pace, or running a 22min 30sec Parkrun 64 times in a row.

Former GB runner James Elson, a veteran of 13 24hr races, says: “Physically and psychologically it’s the most pure running format. The joy and satisfaction of a 24hr race is in its difficulty.”

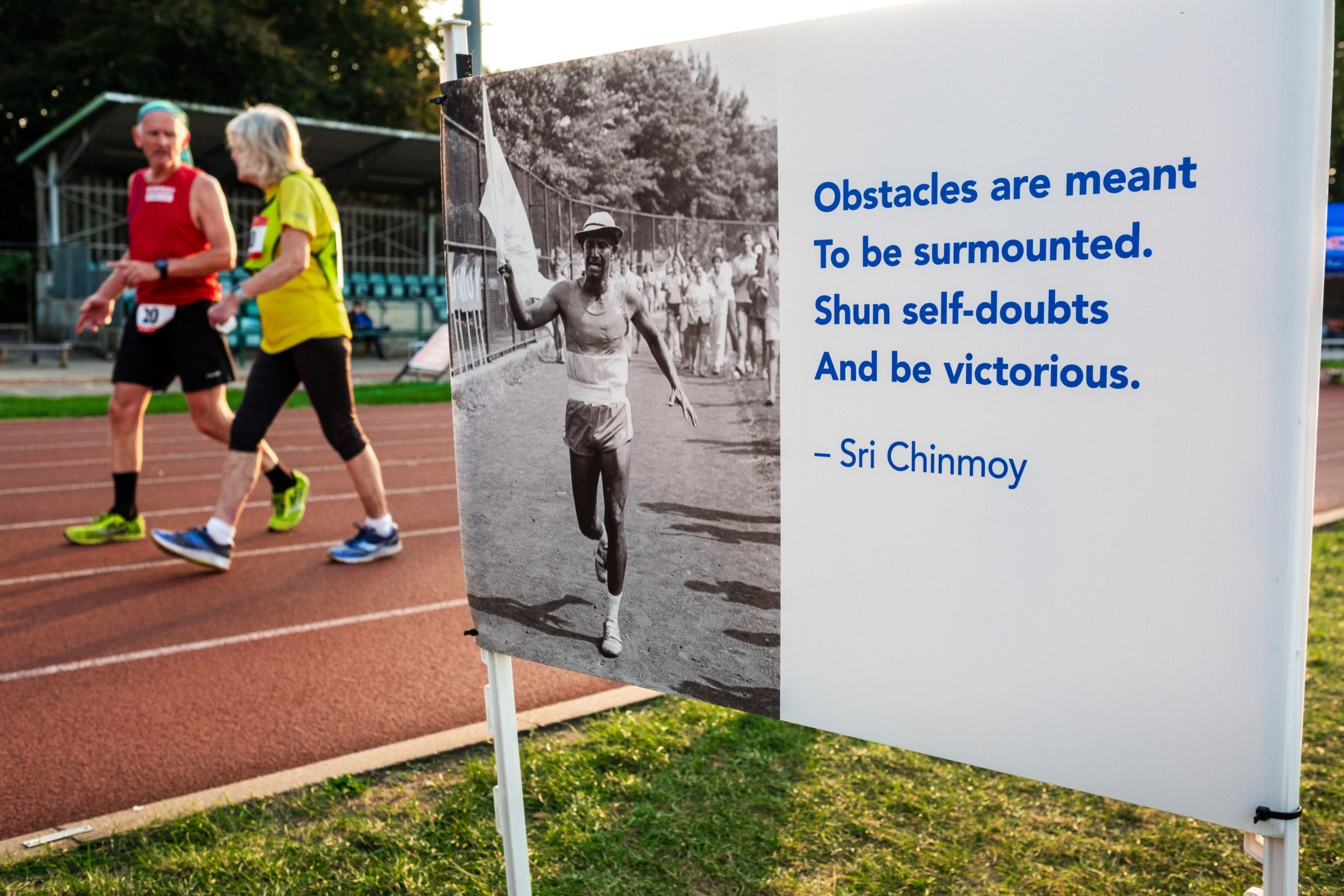

At noon in Battersea, there are nothing but smiles among the 42 runners standing under blue skies on the start line of the Sri Chinmoy Self-Transcendence 24hr Track Race.

Once the gun goes, the clock doesn’t stop. Any time spent stationary – eating, drinking or going to the toilet – is time wasted. Some runners manage all of the above without stopping.

Most charge off as if the race is only one lap, rather than the 527 that the eventual winner completes.

The leaders rattle off a 10k while chatting casually. They have a marathon under their belts inside three and a half hours, a time most recreational runners would be delighted to achieve in a one-off race.

Patricia Seabrook, the oldest competitor at 84, favours a brisk walk. She understands the value of pacing – this is her 19th time at the race, although her personal best of 108 miles from 1996 is no longer in danger.

Why keep coming back? “It’s there to be done,” says the former waitress and minibus driver from Somerset, who has also run 522 marathons. “While I can still do it, I will.”

Ray McCurdy is another playing the long game. A 70-year-old no-nonsense Glaswegian, he has completed 200 marathons and 179 ultra-marathons – anything beyond 26.2 miles – and has been a regular at Sri Chinmoy since 1998. “I’m kind of addicted to them,” he shrugs.

John Turner, the ex-librarian from Kent, is chasing his 17th Sri Chinmoy finish. Despite not taking up running until his 30s, he too has more than 200 marathons to his name. “I like a challenge,” he says with a grin that remains on his face for much of the next 24 hours.

Others are experiencing the format for the first time, drawn by the prospect of pushing their body and mind to places they have never been.

“So many people are scared of what they don’t know. I really embrace that,” says Richard Hall-Smith, a 44-year-old product director from Leicester who started running to lose weight in 2021. “When people ask ‘why?’, I say ‘why not?’”

Michael Stocks, who was so moved by his experience of running 155 miles to win the race in 2018 that he wrote a book called One Track Mind, says: “You’re going to learn a lot about yourself and about what’s possible. I’m seeking to open new doors.”

For the vast majority, winning is impossible – and irrelevant. “It’s about trying your best for every second of that race,” according to 37-year-old Britton.

But surely running around in circles is boring? No change in scenery. No variety in terrain. No crowds cheering you along.

“For much of my running life, the idea of doing a loop seemed quite ridiculous,” says 55-year-old tech entrepreneur Stocks, who then did 622 of them on the way to victory.

Matt Field, who broke Britton’s GB record by running 174 miles in August, says: “I can’t say I felt bored throughout the whole 24 hours.”

He listens to podcasts (ultra-running ones, naturally) and techno music – “it has to be upbeat, fast and continuous” – while Lithuanian Sorokin prefers Metallica blasting in his ears. Hall-Smith is content with “just my thoughts”.

Running repeatedly around the same track has its benefits. You don’t have to carry food or drink, you pass your support crew every few minutes and it is impossible to take a wrong turn, unlike most ultra-marathons.

In Fields’ words, 24hr racing is “definitely not a spectator sport”, which might explain why there is genuine excitement every four hours when all the runners change direction in an attempt to prevent injury.

Two of the pre-race favourites have dropped out by the five-hour mark thanks to illness and a knee problem, and the leader does not make it beyond 10 hours because of chest pains. “The race doesn’t start until 16 hours” is a phrase uttered more than once throughout the day and night by those who have seen it all before.

Yet there are moments of dark humour amid the obvious struggles.

A runner slumps in his chair as the sort of friend we all wish we had mops up his sick from the track with kitchen towel.

At a concert a few yards away in Battersea Park the crowd belt out “I would walk 500 miles”. Perhaps the DJ is an ultra-runner as well as a Proclaimers fan.

The hungry – and fearless – local fox sneaks into an open car by the track. He gets away with an energy gel. It could be worse – last year he pinched a runner’s spare shoe.

Competitors come armed with a mountain of food. Field, an estimator in the construction industry, consumed 10,000 calories during his record run, made up of carbohydrate-rich gels, chocolate, peanut butter and Turkish Delight. He took 12 Calippos for emergencies but needed only three.

Sorokin, who also holds world records for 100km, 100 miles and 12 hours, enjoys cookies, oranges and sandwiches, alternating between sweet and savoury. “I say to my stomach, ‘can you eat a banana?’ He says ‘no, no, no – let’s try something else’.”

Sarah Funderburk, the leading woman as darkness falls at Battersea, is partial to salted potatoes. Brian Robb, the overnight race leader, slurps his way through 57 yoghurt tubes, the sort more commonly seen in a child’s lunchbox.

Samantha Hudson dos Santos Figueira (formerly Amend), a GB 24hr runner and the British women’s 100-mile record holder, has taken it a step further in the past. “I’ve had baby food in a race – because it’s easy to get down.”

In a 24hr race, eating on the go takes on a very literal meaning. But getting food – or “fuel”, as many call it – into your body is not easy, especially after it has taken a pounding for several hours.

“I had such a hard time chewing,” Funderburk, an American now living in London, says after the race. “I made loads of jam tortillas but I just didn’t want to eat them.”

Stocks remembers “gagging even when I looked at food”, while Hudson dos Santos Figueira eats raw ginger to combat nausea. “I just munch on it – it’s disgusting.”

Britton, who coaches some of the world’s best ultra-runners, says: “I eat mostly gels. It’s painful but you’re just getting in as much as you can. They taste OK, but does that matter? I’m not eating to enjoy it.”

Every long training run is eating practice, according to 37-year-old Field. “I did one where I ate a Pot Noodle and a tin of rice pudding.”

He stopped for only 26 minutes of his record-breaking run. Britton was on the go for all but 23 of his.

Although there are portaloos by the side of the track, even those few extra footsteps can seem like an unnecessary diversion. In a 2018 race infamous for its atrocious weather, Stocks remembers shunning social etiquette. “It was late, it was pouring with rain, so why would I bother stopping? I would pee in my pants.”

Lined up along the edge of the track are the support crews – normally a partner or friend who has sacrificed their weekend to pull an all-nighter.

Some runners arrive with little more than a plastic bag of snacks and a camping chair. Others operate out of the boot of their car. The best prepared bring a gazebo, fridge and spreadsheet containing a scientific nutrition and hydration strategy.

“I’ve done this a few thousand times,” smiles Rolf Schatzmann as he steps smoothly into the inside lane and hands his wife, Bernadette Benson, an electrolyte drink he has just prepared. She doesn’t need to break stride.

Part of the role of the crew is to offer encouragement and provide motivation – but they must choose their words carefully.

“Never ask ‘how are you doing?’ because they’re probably in pain,” says Kate Hayden, an ultra-runner who has travelled from Somerset to stand in the rain and help Robb and his partner Roz Glover have the best races they can. She ends up doing the same for three other runners who have no support.

So what should you say? “Ask them ‘what do you need?’” says Hayden – even if that is met more than once with curt replies such as “new legs!” as runners shuffle past.

Shuffling has become the norm as rain lashes down in the early hours of the morning, the runners deep into what is widely regarded as the toughest part of the race.

“At night begins the fight between your body, mind and pain. If you win that, you win the race,” says 43-year-old Sorokin, one of the few professional 24hr runners in the world.

Elson describes it as “deep physical and psychological pain” and says the period from eight to 20 hours is “absolutely horrendous”.

“The biggest challenge is mental. Convincing your brain is absolutely essential,” says Stocks, who works with a sports psychologist. “I’m having this constant argument in my head. The voice is telling me ‘Stop, you don’t need to do this. That’s sore. This is sore. You’ve done enough. This is not that important.’ You have to head that voice off at the pass.”

Britton says: “When you do a 5k your body is screaming at you to stop. In a 24hr your body is whispering the entire time. It’s a constant nag.”

John Pares, former Commonwealth 24hr champion and now GB team manager, pulled out of a race once because of blisters. “The guy looking after me took my shoes off and said ‘there aren’t any blisters’. I could see blisters on my feet. This is how your unconscious mind comes up with tactics to fool your conscious mind.”

Almost a quarter of the field have dropped by 2am, some to injury, some broken by the weather. Benson, a 55-year-old Canadian child psychologist who has travelled from Australia for this race, writes later that she “finally lost the will to live after 13.5 hours”.

Despite sitting in second place throughout the night, Funderburk says afterwards: “Many times I wasn’t sure I was ever going to finish.”

How do runners convince themselves to carry on when, in Elson’s words, “there is absolutely no reason to stay out there”?

“You can’t do it for fame or money because there is none,” says Field. “You’ve got to have a why.”

Glover, a charity worker from Bristol, says it is a privilege to see others achieve their goals – “be it a new distance, a 100-mile personal best or to just battle the demons that tell them to stop”.

Hudson dos Santos Figueira picks her favourite motivational quotes from a jar. “I also pinch myself or put Deep Heat on so it burns. In trail races I deliberately run through stinging nettles.”

Britton grins his way through the pain. “Smiling impacts your perception of effort – studies have shown it,” he says. “It sends a message through your body that things aren’t as hard as they are.

“Everyone is hurting. Who can suffer the least? Who can enjoy it? I love those bits. A good 24hr performance isn’t made when you’re feeling good and moving well. It’s made in the tough moments.

“If you’ve got a very strong mindset, you’re going to go further than a very fit person.”

The rain in London is torrential. The timing clock is broken. A gazebo has blown away. Even the hardy Seabrook has gone for a nap in her car. “She’s not normally that sensible,” says her daughter Theresa.

Amid the deluge, the determination of the runners is nothing short of astonishing.

The shivering Robb, a 40-year-old software engineer from Bristol who decided not to bring a jacket despite a weather warning on the forecast, shuffles forward trying to protect his lead. He has finally been persuaded that a bin-bag gilet is better than nothing.

Glover, who is partially sighted and has a congenital heart defect and curvature of the spine, marches on despite blisters all over her feet. She only took up running because she could not drive her daughter, who is deaf, to a special class. Now 51, this is Glover’s 20th 24hr race and she has run more than 100 ultra-marathons. She will rack up 89 miles.

McCurdy keeps grinding his way to 46 miles, wrapped in the knee-length standard-issue red coat he wore during his days as a newspaper seller. “I’ve had this since 1993,” he says proudly.

Per Audun Heskestad looks as fresh as a 69-year-old in a soggy blue poncho can. He will end the race with four Norwegian records and 108 miles in his legs.

A strange paradox of 24hr races is that the faster you are, the harder it is – without the pay-off of finishing sooner. And runners’ determination to push beyond their limits can pose a different set of problems.

“When I ran for GB one of my team-mates was turning yellow because his kidneys were going into malfunction,” says Stocks.

“I had blood in my vomit in one race,” says Britton, who nevertheless carried on.

“At one race an athlete passed out. Luckily one of our athletes was a paramedic, so he had to jump into paramedic mode.

“People can put themselves in very bad places. If you’re having a good race it’s more likely you’ll run yourself into unconsciousness.”

Adversity visibly brings the runners together in Battersea, whether it be a fist bump while overtaking, or pausing mid-track to celebrate others reaching 100 miles. In endearingly low-key fashion, the landmark moment takes place besides a bin.

Aside from the usual blisters, limps and throbbing limbs, most runners escape relatively unscathed. Simon Bennett, a 65-year-old semi-retired writer from Pontefract, shrugs off a suspected case of trench foot as if he had stubbed his toe.

“I love the shared suffering,” says 42-year-old Elson, who runs a company that organises ultra-marathons. Stocks says: “We’re a community doing this crazy thing. It’s this little ecosystem of life.”

Even the volunteers and crew are a special breed. One has swum the English Channel seven times. Another is a former British cycling hill-climb champion. Race referee Hilary Walker once held the 24hr and 48hr world records and is a member of the Ultra-running Hall of Fame. Pam Storey, who is 76 and crewing two runners, has more than 200 marathons and 24 24hr races on her CV.

One of only three 24hr track events each year in the UK – along with Crawley, organised by Storey, and Gloucester – the race was founded in 1989 by the late spiritual guri Sri Chinmoy, who promoted meditation and physical activity.

Despite the Self-Transcendence tagline, few runners will reach an elevated state within 24 hours – that’s where a 3,100-mile race comes in handy – but the event serves as mindfulness for some.

“It’s like therapy,” says 45-year-old Hudson dos Santos Figueira, who works in IT. “I’ve had a lot of bad experiences – my husband passed away and I’ve had a lot of deaths close to me. I get that sense of comfort when I run.”

Stocks says: “The dream is to be in the zone as much as possible. You have periods when you will lose portions of time.”

The race does not make a profit – the number of runners is capped because of limited space on the track – but race director Shankara Smith says she will “keep doing it for as long as the runners want to do it”.

“I find it inspirational to see what people can do,” she says. “When you reset your expectations it’s amazing.”

Spirits on the track soar as the sun rises and the rain stops.

“That was the best place in the world – it was magical,” says Hall-Smith, who had to spend half an hour in a hot shower at 4am to stave off hypothermia.

Spurred on by the news that she is only one lap behind Robb, Funderburk ups her pace. Her partner and support crew Sean Collum is not surprised. “She’s so competitive,” he says. “We played board games on our first date – she absolutely hammered me.”

By 7am Funderburk has taken the lead and will never relinquish it. Cheered on by members of her running club, the 42-year-old who works in medical communications will become only the third woman in history to win the race. In her first 24hr event, she covers 131 miles, enough to qualify for the US team. By a curious quirk of fate, it marks 10 years since her first half-marathon – a mere 13.1 miles.

The final few hours bring a joyous atmosphere. Friends arrive bearing good wishes and, in Funderburk’s case, hash browns. Smiles are back and layers are off. Robb’s bin-bag gilet is no more.

As the race enters the last hour, those who resembled zombies not so long ago are now running like Mo Farah. Some even manage a sprint in the dying seconds, desperate to bag as many miles as they can.

When the end does come, after 24 of the toughest hours of their athletic lives, there is no glorious finish line or roaring grandstand. Instead, runners must stop wherever they are and place a small pot of sand by the track.

Although electronic chip timers record runners’ completed laps, the unfinished final loop is measured – to three decimal places – by a race adjudicator with a wheel straight from a 1990s PE lesson.

Funderburk’s first thoughts when the race ends? “Absolute, utter relief.”

For Hall-Smith, it is pride. “It’s like you can step away and shake your own hand and say well done,” he says. “We don’t do that enough in life.”

Almost all the 29 runners who have survived the race collapse to the ground. Others have to be helped into chairs. At the modest presentation ceremony, most have their small trophy brought to them because they can barely stand to collect it.

“Sometimes in training you think what you will do when you finish – raise your hands, smile, punch the air,” says world record holder Sorokin. “In reality, you just turn off like a robot.”

Funderburk says a day later: “My feet and ankles are a mess. I’m still not sure when I’ll be able to walk.”

Stocks had to crawl up the stairs at home, needed help getting dressed and was slurring his words for days after his best 24hr race.

So why – just why – would any normal person put themselves through all this?

“Imagine being described as normal,” says Britton. “That would be rubbish, wouldn’t it?”