A new translation of cuneiform relics from the second millennium B.C. highlights the warnings that astrologers saw in eclipses.

It was good to be the king in ancient Babylonia, unless, of course, an eclipse occurred during his reign. Such an event foretold revolt, rebellion, defeat in war, loss of territory, plague, drought, crop failure, locust attacks or even the king’s death. Should the last omen be foretold, the king would go into hiding and a substitute — say, a prisoner or a simpleton — would be installed until the danger had passed. To appease the gods, someone would have to die, so upon the return of the true king, the substitute would be executed.

The people of Mesopotamia in the second millennium B.C. attached a prophetic significance to celestial events. Eclipses were generally understood to be angry messages from the gods. “The reading of omens was how the Babylonians made sense of the world,” said Andrew George, an Assyriologist and emeritus professor at the University of London whose translation of the epic of Gilgamesh is one of the most widely read.

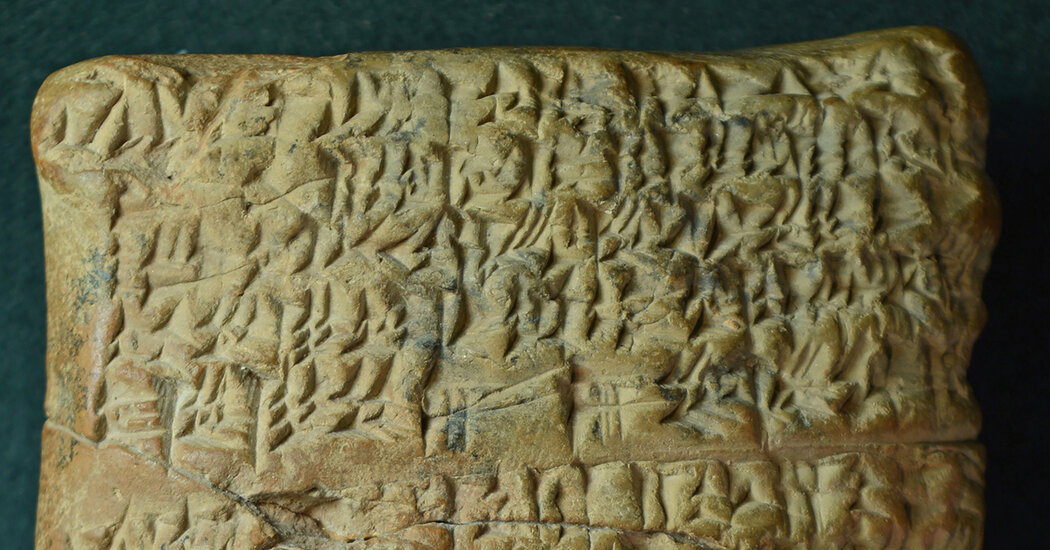

Dr. George led a study published this month in the Journal of Cuneiform Studies that deciphered a set of four tablets covered in cuneiform script and have been held by the British Museum since the late 1800s. The clay slabs most likely came from Sippar, a prosperous city on the banks of the Euphrates, in what is now Iraq. They are dated to about 1894 B.C. to 1595 B.C.

The artifacts, a compendium of Babylonian astrologers’ observations of lunar eclipses, reveal a series of ominous predictions about the deaths of kings and the destruction of civilizations. “The purpose of the omen texts was to figure out what the gods wanted to communicate, good or bad, so as to take action to avoid any trouble ahead,” Dr. George said.

The idea was that earth and sky were mirror images, so happenings in the heavens had counterparts on land. Which is why an eclipse of the sun or moon signaled that a great terrestrial figure would, in some way, be eclipsed: For instance, a king would die. “It is possible that this theory arose from the coincidence of an eclipse and a king’s death — that is, actual experience early in Mesopotamian history,” Dr. George said. “But it is also possible that the theory was developed entirely by analogy. We cannot know.”

The Babylonians saw portents everywhere, which accounts for numerous references in the tablets to the flight and behavior of birds, the patterns made by dropping oil into water, smoke rising from incense burners and encounters with snakes, pigs, cats and scorpions. There are 61 predictions on the newly-translated tablets that vary from warnings about natural disasters (“An inundation will come and reduce the amount of barley at the threshing floors”) to unnatural chaos (“Lions will go on a rampage and cut off exit from a city”). The most poignant predictions describe desperation in time of famine: “People will trade their infant children for silver.”