Specimens of what appear to be the largest eurypterid species found in Australia could shed light on the sudden extinction of the massive arthropods.

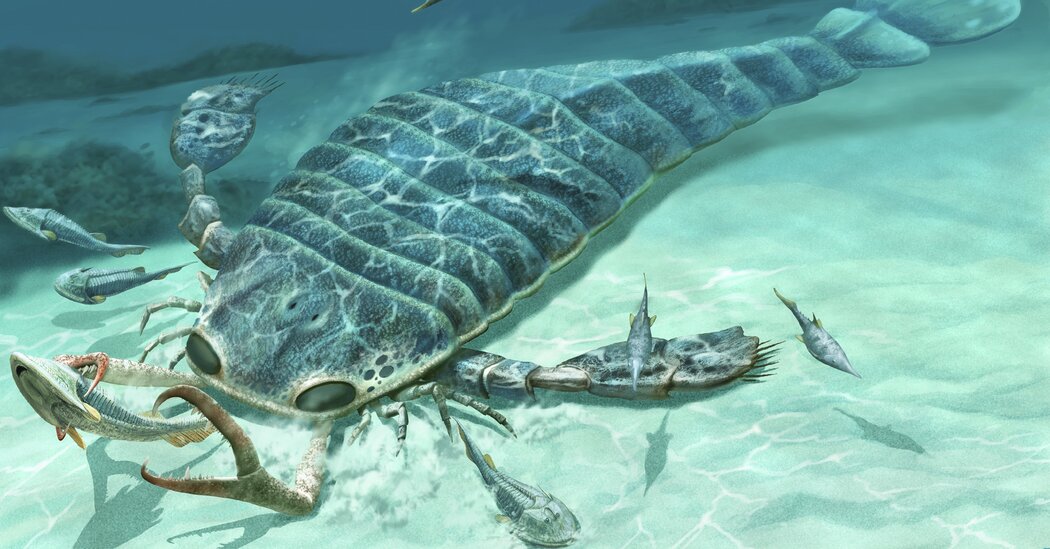

Most modern scorpions would fit in the palm of your hand. But in the oceans of the Paleozoic era more than 400 million years ago, animals known popularly as sea scorpions were apex predators that could grow larger than people in size.

“They were effectively functioning as sharks,” said Russell Bicknell, a paleobiologist at the American Museum of Natural History.

New research by Dr. Bicknell and colleagues, published Saturday in the journal Gondwana Research and relying on Australian fossils, reveals that the biggest sea scorpions were capable of crossing oceans, a finding that is “absolutely pushing the limits of what we know arthropods could do,” he said.

What are commonly known as sea scorpions were a diverse group of arthropods called eurypterids. They came in many shapes and sizes but are perhaps best known for their largest representatives, which could grow to more than nine feet long. With huge claws, a beefy exoskeleton and a strong set of legs for swimming, the larger sea scorpions most likely ruled the seas.

However fearsome these arthropods must have been to Paleozoic prey, they went extinct without much of a bang. The fossil record of eurypterids peaked in the Silurian period, which started about 444 million years ago, and they then abruptly died out after the early Devonian period ended about 393 million years ago.

That sudden turn of fate has left scientists bewildered.

“They appear, they start doing really well, they get very big, and then they go extinct,” said James Lamsdell, a paleobiologist at West Virginia University who was not involved in the study. “For a while they were so dominant, and then they just burned out.”