Like Olympic cyclists, fish expend less effort when swimming in tight groups than when alone. The finding could explain why some species evolved to move in schools.

You’ll catch it during the Olympics this weekend: scores of cyclists banding dangerously close together on a flat road during a race. The formation, known as a peloton, allows riders in the middle to maintain the same speed as those on the periphery, but by using less power.

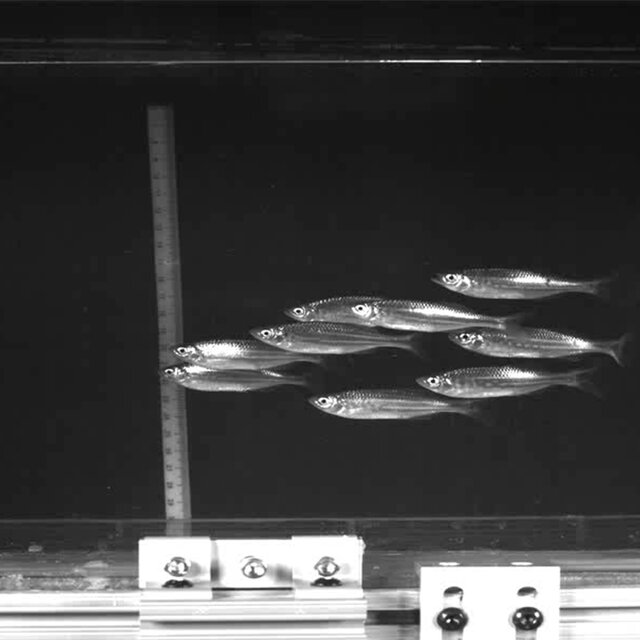

In June, a group of researchers showed that a similar effect occurs with fish in turbulent water. Fish swimming in schools, the team realized, expend less energy than those traveling solo. The team’s study, published in the journal PLOS Biology, is one of the first to directly measure how schools of fish are affected by turbulence.

“To some degree, this makes sense,” said Rui Ni, an engineer at Johns Hopkins University and an author of the new study. “When an environment gets tougher, you group together.”

The findings could lead to a better understanding of how external factors that cause water turbulence can affect fish populations. It may also someday inspire new technologies, like underwater vehicles or flying drones, that are designed to move in groups as a way to reduce their energy use.

Many animals participate in what scientists refer to as collective movement. Insects swarm to mate more effectively; birds flock for better navigation and defense against predation. But scientists have been torn over whether acting as a group reduces the amount of energy each individual expends, or increases it.

The researchers of the new study hypothesized that fish inside schools might be sheltered from the small whirlpools, or eddies, that create aquatic turbulence, and with that protection be able to maintain pace with less effort.