The rock, studied by NASA’s Perseverance Rover, has been closely analyzed by scientists on Earth who say that nonmicrobial processes could also explain the features.

Did NASA’s Perseverance Rover just discover remnants of ancient life on Mars?

Scientists working on the mission are too cautious to claim so, but they are over-the-moon excited about the most intriguing rock that the rover has come across in more than three years of exploring Mars.

The rock, which scientists named Cheyava Falls, possesses a chemical composition and structures reminiscent of what microbes might have left behind when this area was warm and wet several billion years ago, part of an ancient river delta.

“We found something we’ve never seen before, which will give our scientists so much to study,” Nicola Fox, the associate administrator of NASA’s science directorate, said in a news release.

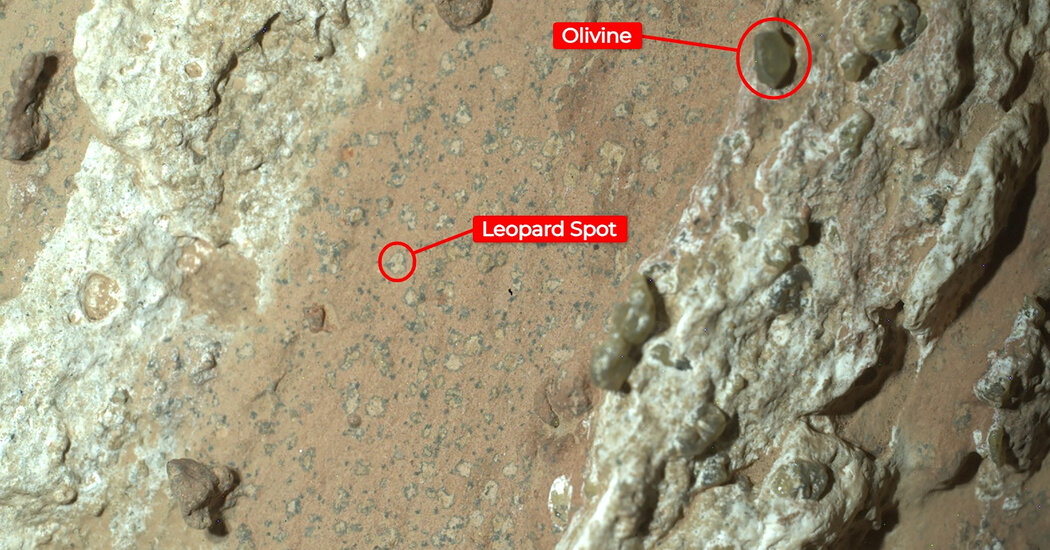

Within the rock, Perseverance’s instruments detected organic compounds, which would provide the building blocks for life as we know it. The rover also found veins of calcium sulfate — mineral deposits that appear to have been deposited by flowing water. Liquid water is another key ingredient for life.

Perseverance also spotted small off-white splotches, about a millimeter in size, that have black rings around them, like miniature leopard spots. The black rings contain iron phosphate. Similar features are seen in rocks on Earth, and most are the result of chemical processes caused by microbes.

With the limited capability of the robotic rover’s instruments, scientists cannot say anything more conclusive and cannot rule out explanations caused by nonliving geological processes. But one of the key parts of Perseverance’s mission is to drill samples of interesting rocks for a future mission to bring samples back to Earth for scientists to study with state-of-the-art instruments in their laboratories.

The Mars sample return mission, however, has hit major developmental and cost snags, putting it years behind schedule and billions of dollars over budget.

“The bottom line is that $11 billion is too expensive,” Bill Nelson, the NASA administrator, said in April. “And not returning samples until 2040 is unacceptably too long.”

Space agency officials announced that they were seeking to solicit ideas from outside companies on how to bring rocks back sooner, at a lower cost. NASA later awarded contracts to seven companies to study the problem. NASA centers are also working on three studies of their own.

This is a developing story and it will be updated.