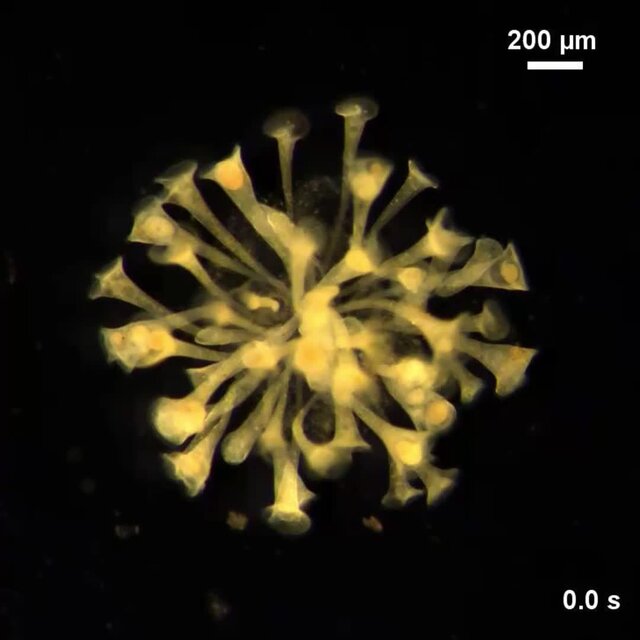

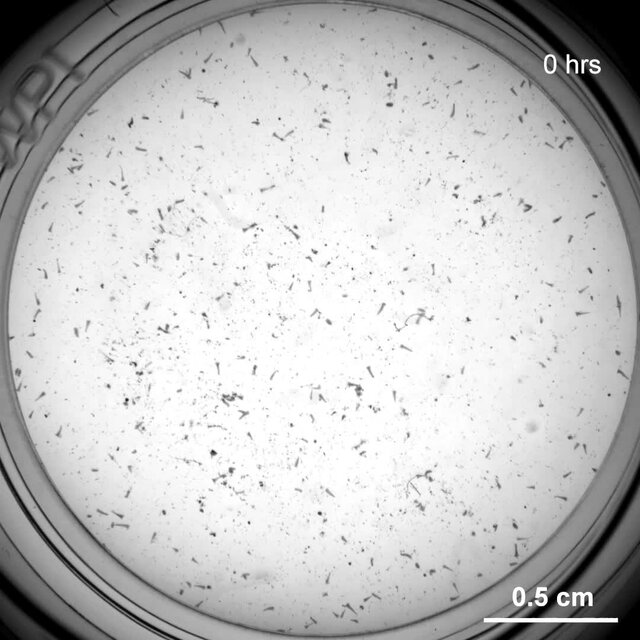

Under microscopes, scientists found that giant single-cell organisms were able to vacuum up more food when they are stuck together.

For a creature made up of only a single cell, the stentor is a giant. This trumpet-shape organism is among the largest unicellular organisms, stretching as long as a sharpened pencil tip. But sometimes it has a hard time vacuuming up the swimming bacteria and microscopic algae it eats to survive.

New research reveals that stentors, which are part of a group called protists, may address this challenge by eating “family style.” In a paper published on Monday in the journal Nature Physics, scientists shared the discovery that colonies of stentors can make water flow more quickly around them, helping them suck up more prey.

The new findings suggest that, although they lack neurons or brains, stentors can cooperate with one another.

“These single-cell organisms can do things that we assume are limited to more complex organisms,” said Shashank Shekhar, a biophysicist at Emory University in Atlanta who is the lead author of the new paper. “They form this higher order structure, like what we do as humans.”

Scientists believe that the ability of single-cell creatures to form groups was a key step that led to the eventual evolution of multicellular life on Earth. And the new findings spotlight the role played by physical conditions — and the interplay of predators and prey — in these cellular collaborations.