It wasn’t the size of human brains that distinguished people from apes, he theorized, but the way they were organized. He found a creative way to prove it.

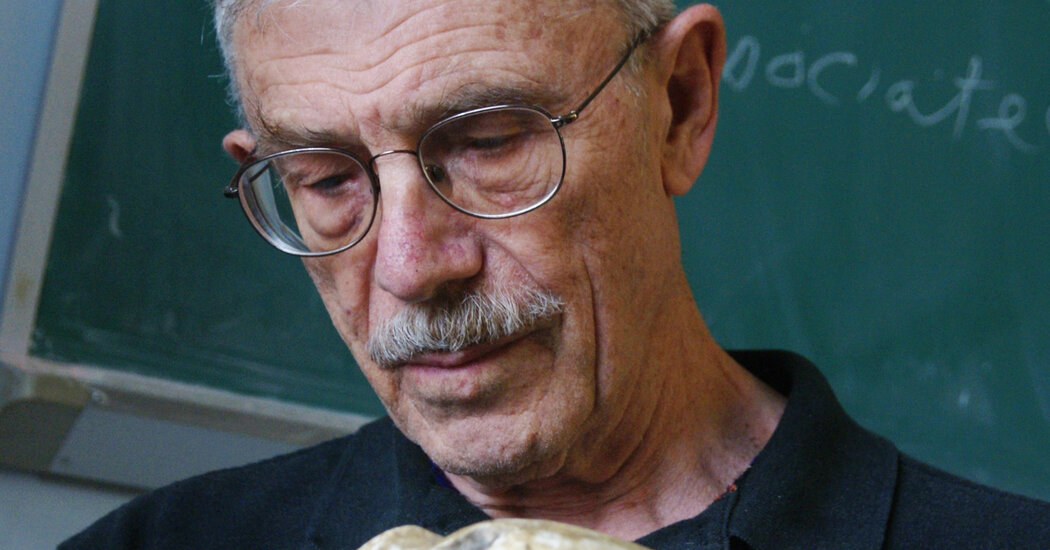

Ralph Holloway, an anthropologist who pioneered the idea that changes in brain structure, and not just size, were critical in the evolution of humans, died on March 12 at his home in Manhattan. He was 90.

His death was announced by Columbia University’s anthropology department, where he taught for nearly 50 years.

Mr. Holloway’s contrarian idea was that it wasn’t necessarily the big brains of humans that distinguished them from apes or primitive ancestors. Rather, it was the way human brains were organized.

Brains from several million years ago don’t exist. But Dr. Holloway’s singular focus on casts of the interiors of skull fossils, which he usually made out of latex, allowed him to override this hurdle.

He “compulsively collected” information from these casts, he wrote in a 2008 paper. Crucially, they offered a representation of the brain’s exterior edges, which allowed scientists to get a sense of the brain’s structure.

Using a so-called endocast, Dr. Holloway was able to establish conclusively, for instance, that a famous and controversial two-million-year-old hominid fossil skull from a South Africa limestone quarry, known as the Taung child, belonged to one of mankind’s distant ancestors.