The chipmaker expects more than $10 billion in foreign sales this year, but the Biden administration is advancing rules that could curb that growth.

In early August, the king of Bhutan, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, traveled from the mountains of his landlocked Asian country to the headquarters of Nvidia, a maker of artificial intelligence chips in the flatlands of Silicon Valley.

King Wangchuck did a two-hour tour and listened as Jay Puri, Nvidia’s head of global business, discussed how Bhutanese investment in data centers and Nvidia chips could combine with the kingdom’s biggest natural resource, hydropower, to create new A.I. systems.

The pitch was one of dozens that Nvidia has made over the past two years to kings, presidents, sheikhs and government ministers. Many of those countries went on to pour billions of dollars into government efforts to build supercomputers or generative A.I. systems, hoping to gain a competitive foothold in what could be the century’s defining technology.

But in Washington, officials worry that Nvidia’s global sales spree could empower adversaries. Now the Biden administration is working on rules that would tighten control over A.I. chip sales and turn them into a diplomatic tool.

The proposed framework would allow U.S. allies to make unfettered purchases, adversaries would be blocked entirely, and other nations would receive quotas based on their alignment with U.S. strategic goals, according to four people familiar with the proposed restrictions, who did not have permission to speak publicly about them.

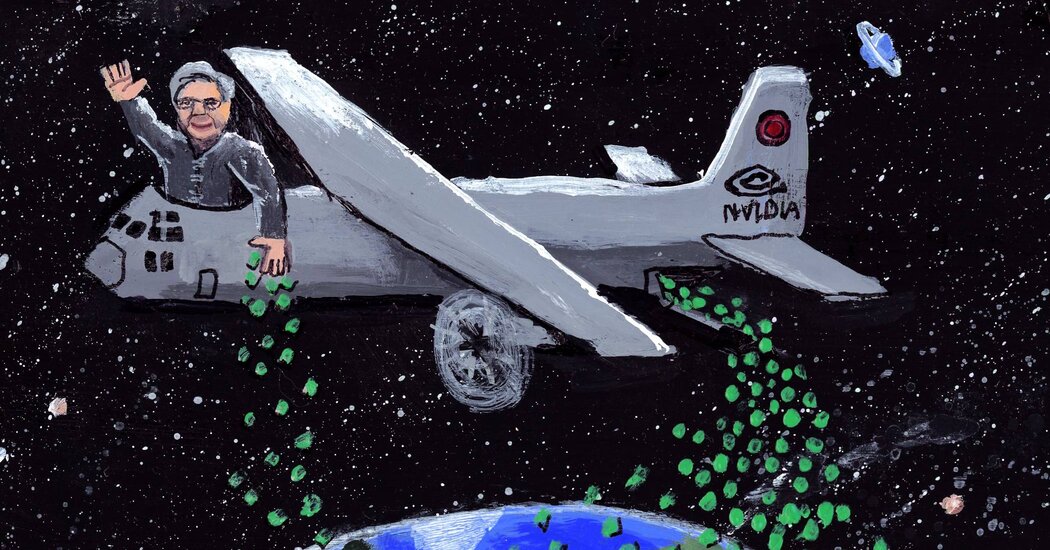

The restrictions would threaten an international expansion plan that Nvidia’s chief executive, Jensen Huang, calls “sovereign A.I.” Mr. Huang has hopscotched the globe this fall, logging over 30,000 miles in three months, and the company expects to make more than $10 billion in sales this year from countries outside the United States.