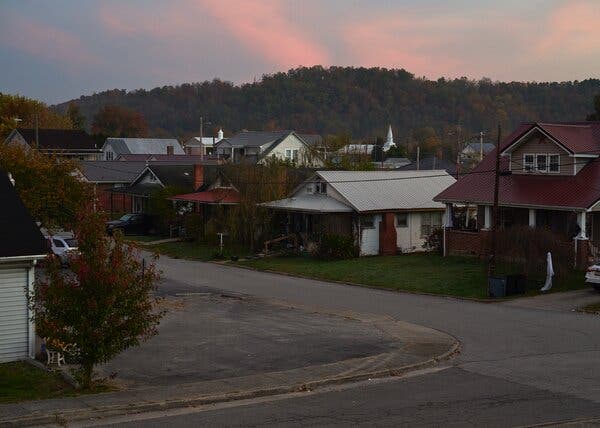

Louisa, Ky., is a small town of about 2,600 on the border of West Virginia with a single pair of railroad tracks running through it. If you follow these tracks south, against the flow of the Big Sandy River, you’ll go between the public library and the Main Street Park and over Lick Creek, one of the manifold creeks that web eastern Kentucky like capillaries. Follow Lick Creek past a baseball diamond and a pawnshop and you’ll arrive behind an ordinary gray mobile home in a small lot of grass where Ingrid Jackson was living in the fall of 2023. The days were still long and the afternoon sun settled gently on nearby mountains, turning leaves a lambent red. Reedy gospel music played from inside the trailer, announcing Jackson’s presence as she opened the door. Her hair, normally figured in light brown curls, was packed into a shower cap. She smiled from the entryway. It was a smile difficult not to smile back at.

Listen to this article, read by Eric Jason Martin

Jackson had never lived in a trailer before, or a small town. She was born in Louisville, the daughter of a man with schizophrenia who, in 1983, decapitated a 76-year-old woman. Jackson was 1 at the time. In 2010, at 27, she was in a car accident and was prescribed pain pills. Not long after that, she began using heroin. Over the next decade she went through nine rounds of addiction rehab. Each ended in relapse. Her most recent one came in 2022 after her son was sentenced to life in prison for murder; he was 21. In Louisville on Christmas Day she called a residential rehab company named Addiction Recovery Care, which has its headquarters in Louisa. So now she was here, in Appalachian coal country, in a trailer along Lick Creek, in a town a tiny fraction the size of her home city, working as a nursing assistant in a nearby nursing home, sharing a trailer with Latasha Kidd, a local woman 12 years her junior with a mountain accent, a fade and blood-orange bangs. “This is culture shock,” Jackson said. “I’m a city girl, and there’s not a lot of us around, and I’m like: Mama!”

Jackson and Kidd were about as different as you could make them. Jackson was Black, Kidd white; Jackson outgoing, Kidd reserved; Jackson neat, Kidd messy; Jackson devout, Kidd agnostic; Jackson straight, Kidd queer. Still, they became fast friends in rehab and now, five months out, inhabited a somewhat fragile existence together, in the period of addiction recovery that many people in long-term recovery say is the most difficult: the space between leaving rehab and getting back on your feet. More than a million people in the United States are arrested every year on drug-related charges, and for them, finding a steady job, consistent housing and reliable transportation can be even more difficult than the tremors, hallucinations and nausea of detox. Studies have shown that relapse rates for people in recovery may be as high as 85 percent within the first year. Another woman with whom Kidd and Jackson went through recovery, who was supposed to live with them, relapsed and overdosed the day before moving in.

Jackson often worried that something similar might happen to Kidd, who had struggled with addiction so long that, until recently, she didn’t know how to pay her bills. At 29, Kidd hadn’t yet held a full-time job. “So I have to push her sometimes,” Jackson said. “ ’Cause when I want to go in my own direction, I don’t want Tasha to be left upside-down.”