Genetic tests showed that certain patients were predisposed to brain injuries if they took the drugs. That information remained secret.

By 2021, nearly 2,000 volunteers had answered the call to test an experimental Alzheimer’s drug known as BAN2401. For the drugmaker Eisai, the trial was a shot at a windfall — potentially billions of dollars — for defanging a disease that had confounded researchers for more than a century.

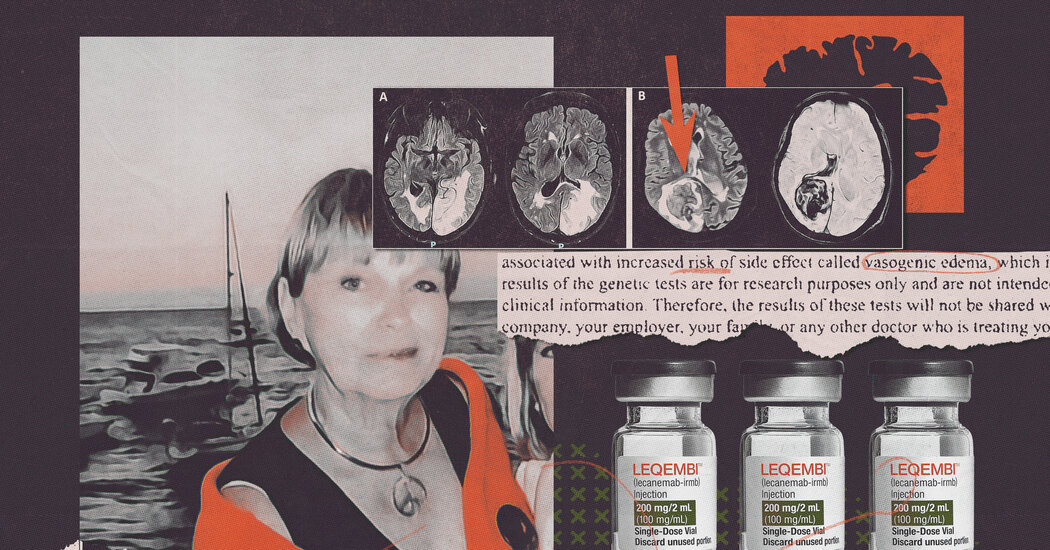

To assess the drug’s effectiveness and safety, Eisai sought to include people whose genetic profiles made them especially prone to develop Alzheimer’s. But these same people were also more vulnerable to brain bleeding or swelling if they received the drug.

To identify these high-risk volunteers, Eisai told everyone that they would be given a genetic test. But the results, the company added, would remain secret.

In all, 274 volunteers joined the trial without Eisai telling them they were at an especially high risk for brain injuries, documents obtained by The New York Times show.

One of them was Genevieve Lane, a 79-year-old resident of the Villages in Florida who died in September 2022 after three doses of the drug, her brain riddled with 51 microhemorrhages. An autopsy determined that the drug’s side effects had contributed to her death. Her final hours were spent thrashing so violently that nurses had to tie her down.

Another high-risk trial volunteer died, and more than 100 others suffered brain bleeding or swelling. While most of those injuries were mild and asymptomatic, some were serious and life-threatening.